11-23-2024:Scroll down for English

本書は、FFIにおいて、スペイキャスティングの重鎮であられ、先月日本を訪問されたRick Williams博士による近著。 この本について博士から直接お聞きする機会が先月あった。

日本のサケの幼魚は、春、雪解け水とともに海に降り、1~3カ月間、河口近くの沿岸部で過ごしながら遊泳能力や餌を捕獲する能力が養われ、寒流が離岸する初夏までには、オホーツク海へと回遊。割合閉ざされた海域であるオホーツク海は、餌が豊富、競合種が少ないなどの特色がある。オホーツク海に晩秋まで滞在した幼魚は、北太平洋西部へ回遊し、そこで最初の冬を越す。翌年の春になると、幼魚はベーリング海に回遊し、兄貴分の成魚、未成魚たちと合流して、秋季まで過ごす。ベーリング海は、春から秋季にかけて、日本系シロサケが好んで過ごす海域で、ここで回遊しながら餌を捕獲し、大きく成長する。

Hiro: 北海道の水産大学のある先生は、「例年通り海に向かうサケは、水温が上がりすぎたため、北の海に入るまでに力尽きて、他の魚との生存競争に負けているのではないか」と語っています。Williams博士はこれをどう思いますか?

Williams博士: 「北米も温暖化による異常気象が襲い、サケ鱒が冷たい水と豊富な餌場を求めてベーリング海に行き着いた挙句、そこには熾烈な餌の奪い合いが待っていて、そこに日本のサケが巻き込まれた可能性は十分あり、日本のチャムサーモンは、生存競争に負けていた、と言う仮説はあり得ると言っていいね。」

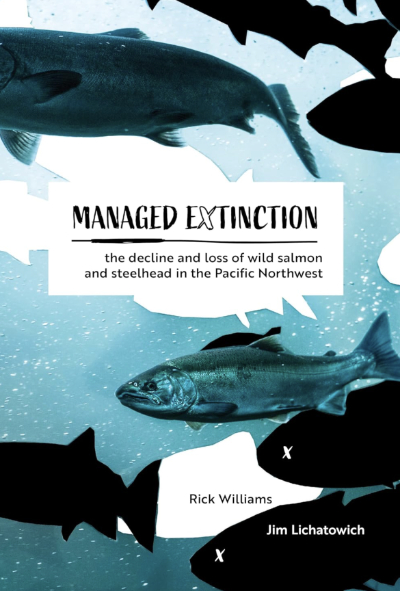

Williams博士の著書のタイトルの「Managed Extinction: 管理された絶滅」の本の主旨は以下。 本書は過去 150 年間に太平洋北西部で野生のサケとニジマスが減少しつつある状況を浮き彫りにしている。現在、多くの個体群が絶滅の危機に瀕しており、特にアイダホ州のスネーク川流域では顕著。コロンビア川とスネーク川の広範囲にわたる生息地の改変と本流ダムがサケとニジマスの減少の一因となっているが、減少するサケの遡上を回復させるために保護対策ではなく養殖場の生産に依存し続けた結果、管理と言う名目が絶滅を進めている。絶滅の危機に瀕した上流域のサケとニジマスの個体群を回復するには、下流スネーク川の 4 つのダムの撤去、河川の生態学的プロセスの回復、および生態学的回復力と管理に重点を置いた新しいサケ管理パラダイムの開発が必要になっている。

今年は、アトランティック・サーモンフィッシングのメッカである、ノルウェーのガウラの釣りが閉鎖されると言う大ショッキングなニュースもあった。私が天塩川で2年前の10月末に行った時には、異常な数のサケがそこにはいた。しかし、今年の11月は、その時の10%にも至らない。これが地球温暖化の有害な影響ではなく、いつものように単に4年ごとに起こる北海道サケの周期的な現象であると期待するのは、楽観的すぎるかもしれない。

This book is a recent work by Dr. Rick Williams, a leading figure in Spey casting at FFI, who visited Japan last month. Last month I had the opportunity to hear directly from the doctor about this book.

Japanese salmon juveniles go down to the sea with meltwater in the spring, and spend 1 to 3 months in the coastal areas near the river mouth, where they develop their swimming ability and ability to catch food, and by early summer when the cold current leaves the coast, they migrate to the Sea of Okhotsk. The Sea of Okhotsk, a relatively closed sea area, is characterized by an abundance of food and few competing species. The juvenile fish that stay in the Sea of Okhotsk until late autumn migrate to the western North Pacific Ocean, where they spend their first winter. In the spring of the following year, the juvenile fish migrate to the Bering Sea, where they join their “big brothers,” adult and immature fish, and spend the rest of the year until autumn. The Bering Sea is a favorite water area for Japanese chum salmon from spring to autumn, where they catch food and grow large as they migrate.

So, I asked Dr. Williams, an authority in this field.

Hiro: A professor at a fisheries university in Hokkaido said, “The salmon that head to the sea as usual are running out of energy by the time they reach the northern seas because the water temperature has risen too much, and they are losing the fight for survival with other fish. What do you think?”

Dr. Williams: In the Bering Sea, Japanese salmon (fish of the Salmonidae family) may suddenly start losing the fierce competition for survival with Pacific North American salmon and trout. North America is also experiencing abnormal weather due to global warming, and it is highly likely that salmon and trout reached the Bering Sea in search of cold water and abundant feeding grounds, and then got caught up in fierce competition for food there, so there is a good chance that the hypothesis that Japanese chum salmon were losing the competition for survival there is valid. “

The main points of Dr. Williams’ book, “Managed Extinction,” are as follows. It refers to the phenomenon of the decline in wild salmon and rainbow trout in the Pacific Northwest over the past 150 years. Many populations are now at risk of extinction, especially in the Snake River Basin in Idaho. Extensive habitat modification and mainstem dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers have contributed to the decline of salmon and rainbow trout, but continued reliance on farm production rather than conservation measures to restore declining salmon runs has led to management leading to extinction. Recovering endangered upper basin salmon and rainbow trout populations requires removal of four dams on the lower Snake River, restoration of river ecological processes, and development of a new salmon management paradigm that emphasizes ecological resilience and management.

This year there was also the shocking news that fishing in Gaula, Norway, a mecca for Atlantic salmon fishing, was to be closed. When I went to the Teshio River two years ago in late October there were huge numbers of salmon there. However, this November, there were less than 10% of what there were then. It may be overly optimistic to hope that this is simply a cyclical phenomenon in Hokkaido salmon that occurs every four years, as it always has, rather than a deleterious effect of global warming.